Interface Drama: A New Way of Telling Stories Through Software

Slides

Transcript

CJ: Hi, I'm CJ.

mabbees: And I'm mabbees!

mabbees: We're hobbyist game developers, and have been making experimental games since the early 00's. We made a go-karting game called Channel Drive, a co-op VR game where you split a headset between three people called “Three Monkeys”, and a waffle-making simulator presented in “smell-o-vision.” Most of these were quick prototypes that we've set aside.

CJ: But in 2019, we found a game concept that piqued players' interest, and also fueled our passion for making it. So we wanted to see it through to a higher level of completion and polish. That game eventually became Terranova, a game set in the early 2000's about fangirls on the internet, released in April this year and is...

mabbees: (whispering cheekily) ...out now on Steam and itch.io!

CJ: When we first made Terranova, we weren't really sure how to describe it to our friends. When they'd ask what we made, we'd say, "We made a cool game!" and then they would say...

mabbees: "Oh, like Super Mario?"

CJ: "No. Not exactly. It's like a...a text-based game."

mabbees: "Oh, like a choose-your-own-adventure. I used to love those books."

CJ: "Sort of,” we said, “but it has characters you can meet in the world. And the choices you make affect their relationships.

mabbees: "Oh, I got it! Like a visual novel."

CJ: But it also has solitaire?!

mabbees: This is usually how our conversations go. But sometimes, our friends will say, “Oh, it's just like...”

(at the same time)

CJ: Hypnospace Outlaw!

mabbees: Secret Little Haven!

(they both look at each other in confusion.)

CJ: And that's when we realized we weren't just struggling to describe our game—we were struggling to describe a genre of games.

Nerd Nite is about diving deep into an unknown world, so allow us to invite you into ours. It's a world where stories and software collide. A world full of esoteric and sometimes very intimate games.

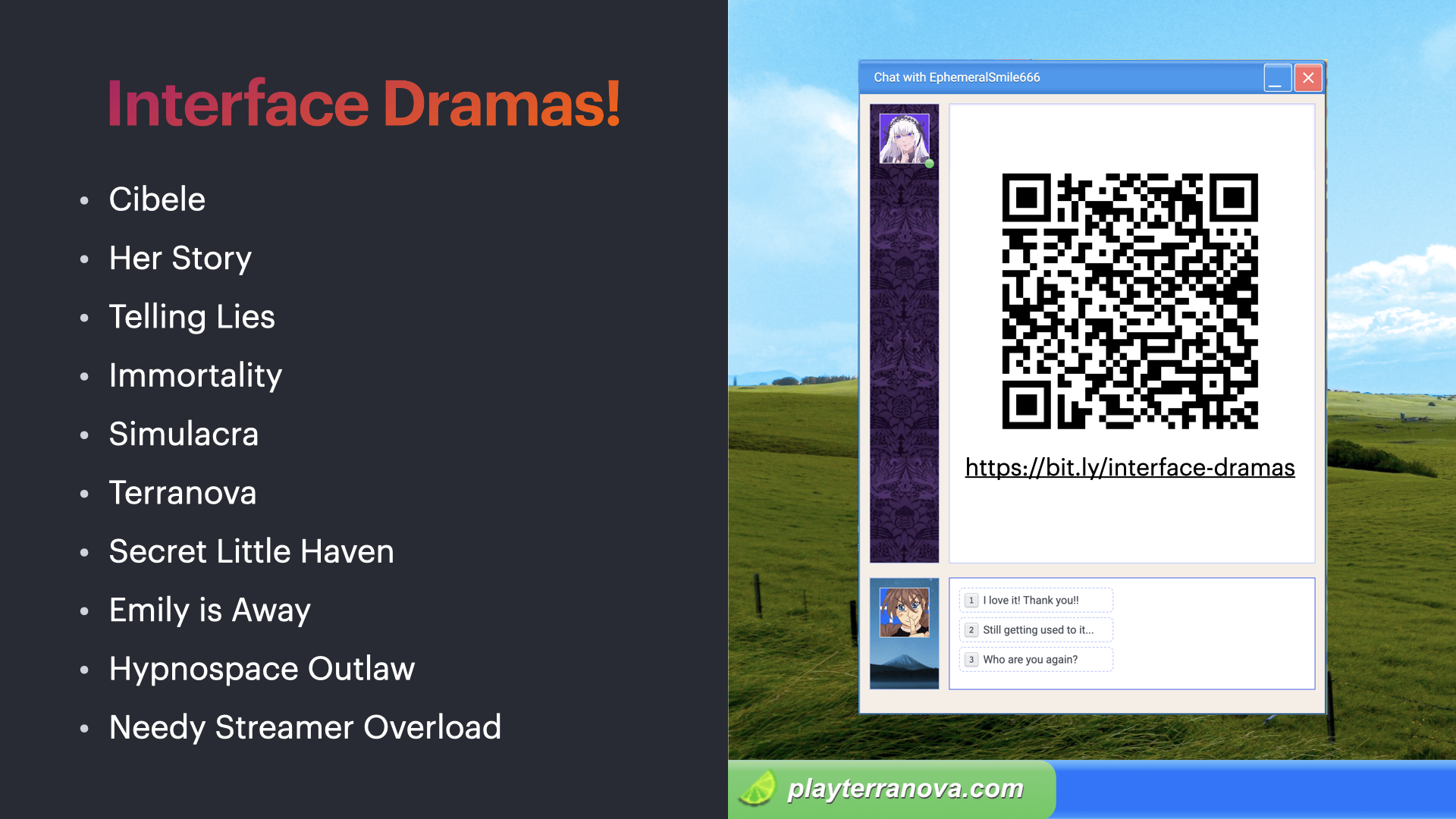

mabbees: Tonight, we’d like to talk to you about a new, emerging genre in video games. Sometimes they are called “desktop simulators,” or “UI games,” but if we may be so bold, we'd like to suggest a new name... interface dramas.

We chose the words “interface drama” because these games use interfaces, which are the interactive parts of technology. Think buttons, scrollbars, and things you can poke and push.

And they use interface to tell dramas, or immersive stories. They are usually incredibly personal and human.

These are some examples. Interface dramas look like the software and apps we use on a daily basis, except they use these interfaces to tell stories.

After playing a lot of these interface dramas, and after developing one to boot, we found four common traits of this genre...

1. You are the main character

We’re not just saying you “control” the main character. When you play Mario, you make Mario run and jump by pressing buttons. But in our game Terranova, where you play as the main character, a high school girl in the year 2004 who goes by Tourmaline online, her actions are the same as yours. There's very little "distance" between the actions you take and the actions Tourmaline takes. When she posts a blog on her PC, you post a blog on your "PC." You cannot see Tourmaline's face in the game—it is assumed that you are Tourmaline. She is meant to be some kind of representation of you, perhaps when you were a teenager.

2. It has an immersive environment focused on story

It has an immersive environment focused on story. In Her Story, a whodunnit game where you play as a detective trying to solve a murder by reviewing old police footage, everything about the interface; the old school windows, the scan lines and the shine on the CRT monitor. This accentuates the feeling of using an old police computer to catch a killer. The interface is telling a story—one of an underfunded police department using old technology. Ohe of the very first clips you search, a woman says, “I didn’t murder Simon,” which immediately begs the question, “then who did?”

(Content Warning: The next image contains flashing lights. Please skip if you are sensitive.)

3. It uses interface elements to add tension to the drama

Simulacra is a psychological horror game about finding someone’s lost cell phone. It creates tension from something mundane by using smartphone interface conventions in an artful way. While the player is trying to do something else, there is no music—it is completely silent. Then—the sudden interruption of a phone call, flashing lights, a creepy ringtone. And the mood of the game goes from calm to deeply anxious.

4. It rewards players for being curious

The game rewards players for being curious. The default of these games isn't necessarily to achieve a task, though if you do, you progress the story; it's to look around and get lost. Hypnospace Outlaw is a game about a fictional software called Hypnospace that allows players to browse the web and check their websites, all while a device is attached to their brainwaves. It's a game about the old-school internet, but it's also about ethical questions in "emergent" technologies, especially ones that have access to our heads.

Check out this page that I found. “Hiding Occult References in Utmost Secrecy?” And it needs a password to access? Think of the interface drama like a sandbox with treasures hidden in it. The purpose isn’t to win; it’s to find all the treasures and unlock the full story.

CJ: At its core, this is what interface drama is: an immersive story told through software and app interfaces. You might ask, “is this really a new genre of game?” So let’s talk about interface dramas in context of other games and what makes them different than say, simulation games or visual novels.

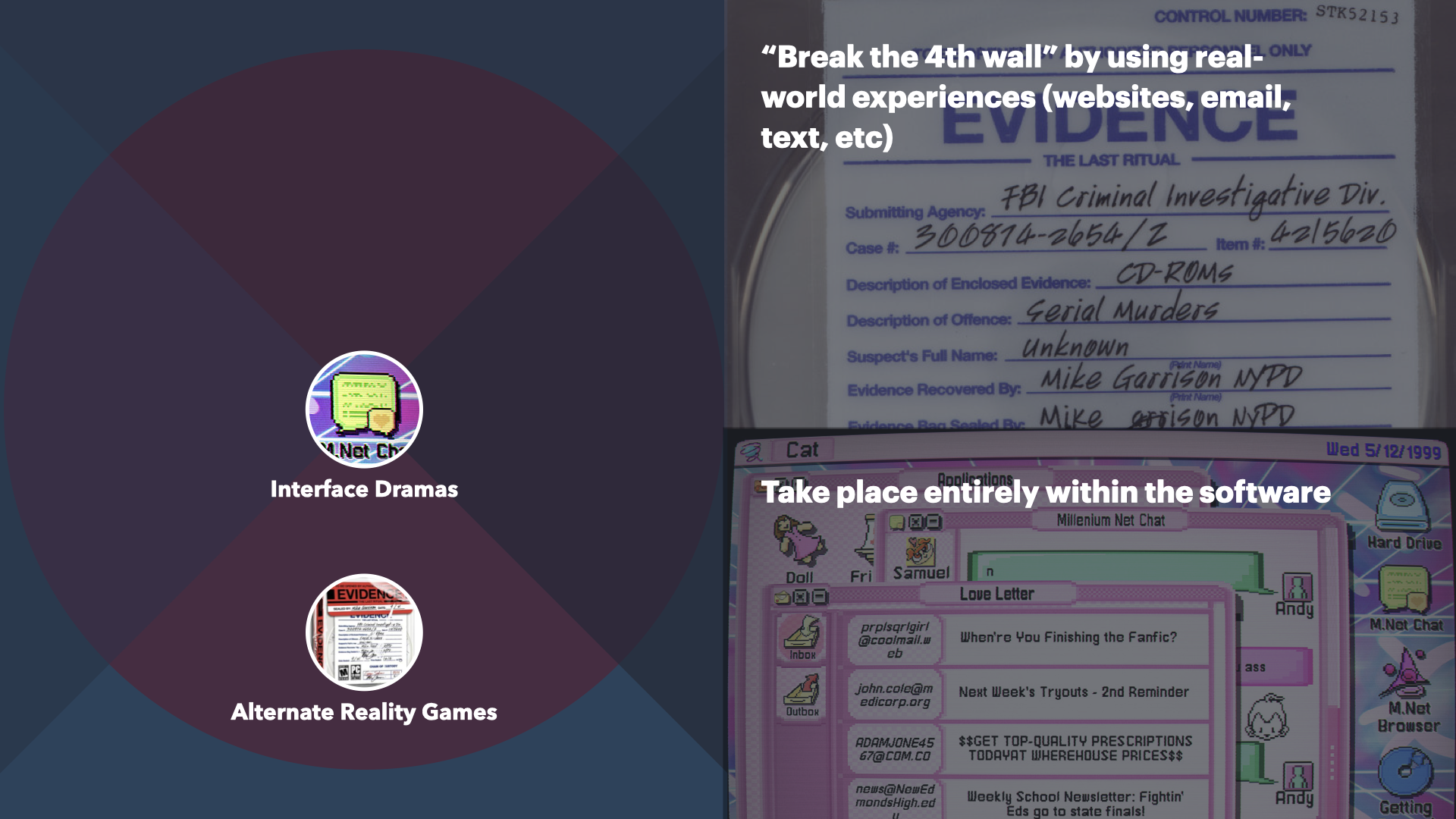

mabbees: Interface Dramas take direct inspiration from many pre-existing genres of games. In the red circle, we have some game genres that are closely related to interface dramas. Simulation games, for example Microsoft Flight Simulator or Densha de Go! are games that simulate real life, like flying a plane or driving a train.

Here's visual Novels, like Higurashi no Naku Koro ni or Doki Doki Literature Club, are games that focus on telling a story that players can (sometimes) influence the outcome of.

And then there's point and click adventures, for example, Secret of Monkey Island or Day of the Tentacle, are puzzle games where a player explores a world and clicks on objects.

We can't forget alternate reality games like Evidence: The Last Ritual and Subtext. These are games that use out-of-game interactions to make the player believe the story happening in the game is also happening in real life, like emailing or calling the player.

Moving outward, there are more distant influences: Interactive Fiction and Text Based Adventure Games. Interactive fiction is a choose-your-own adventure novel; it is primarily text-based and the player can choose different options or commands to interact with the novel and get different endings.

Text-based adventure games like Colossal Cave Adventure and Zork used of natural language processing, technology pioneered by conversation systems that weren’t originally meant for gameplay. With these types of games you could type “light the lantern with the match” and if it noticed that you didn't have a match in your inventory, it would respond, “you aren’t holding a ‘lantern with the match’”. This is a clue for the player to go find a match, and can only be discovered by talking to the game. The gameplay often involved solving puzzles to make progress.

Interactive Fiction, by comparison, has less focus on puzzle solving, and instead asks the player to make choices that can influence the outcome of the story. They expanded on a concept that predates games entirely, and comes from books like Choose Your Own Adventure. With Choose Your Own Adventure books, the book would ask you to flip to a specific page; in interactive fiction you are linked to a particular page in the story.

What's the difference between interface dramas and other genres?

Now that we've introduced each of these genres of games, let’s talk about each of them and how they compare to interface dramas.

Alternate reality games commonly break the 4th wall and pull in other out-of-game experiences. In Evidence: The Last Ritual (2006), the player is a detective investigating the serial killer The Phoenix. The player enters their email and over the course of the game, is emailed clues by the killer, so the game is both played from the disc and via email.

However, in interface dramas the action happens solely within the software. For example, Cybele makes use of email; but rather than using the player’s actual email, they can check Cybele’s email within the game. This is to immerse the player in the feeling of using the software, not to take them out of it.

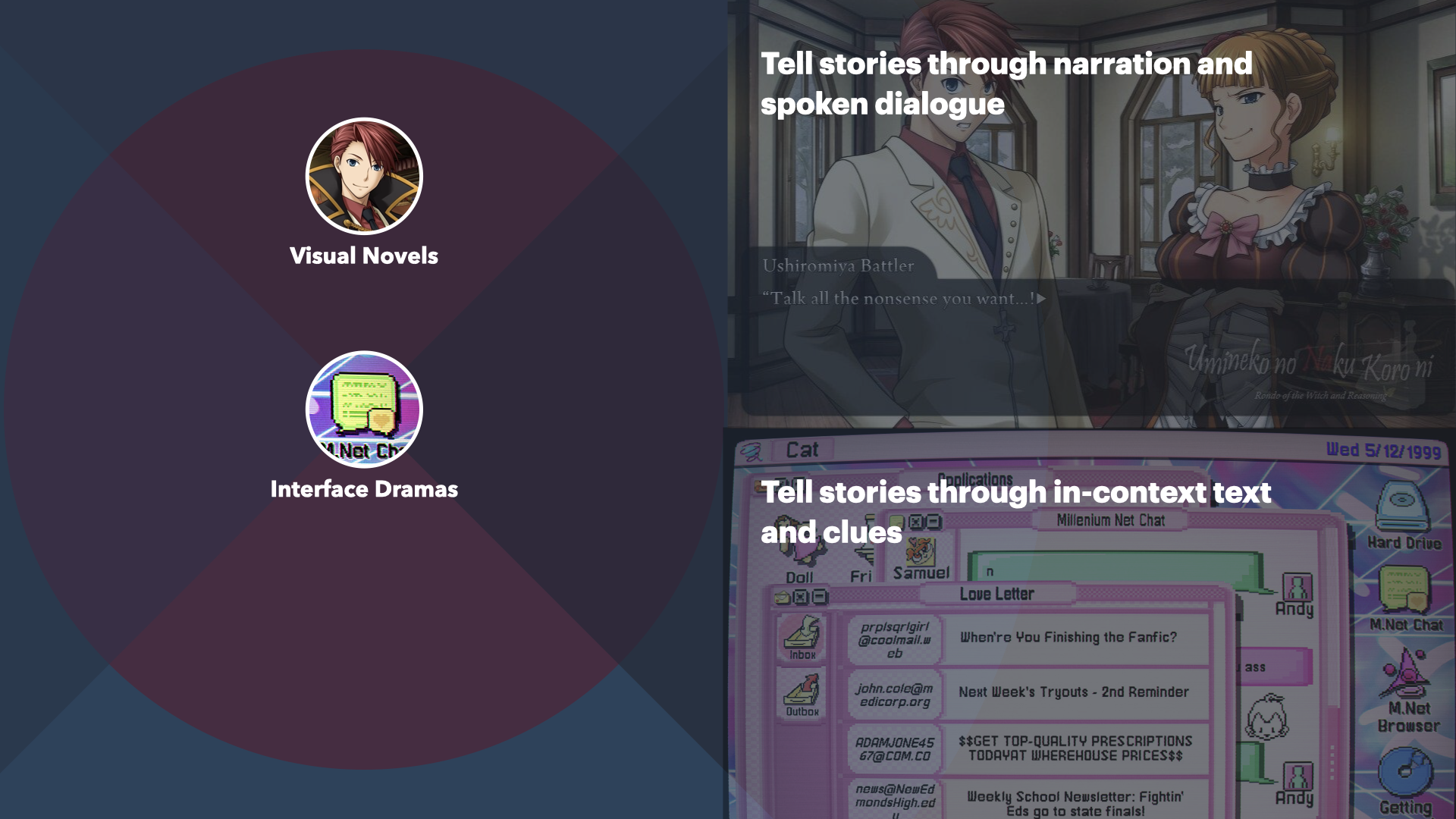

Visual novels tell stories through narration and spoken dialogue. In Umineko When They Cry, the player narrates the story as they experience it, and the characters speak directly to the player. For example, if it was a dark and stormy night and the player meets a golden-haired woman, visual novels would describe the scene in text to the player. For instance, “it was a dark and stormy night when I saw her. Her hair was shiny and gold.”

On the other hand, interface dramas tell stories through in-context text and clues. For example, in Hypnospace Outlaw, you find out that a character has broken up with his girlfriend not because he directly tells you—but because he updates his status as, “sad face” and his girlfriend’s page has changed from a picture of them together to her talking about someone new.

Unlike visual novels, interface dramas show but don't always tell.

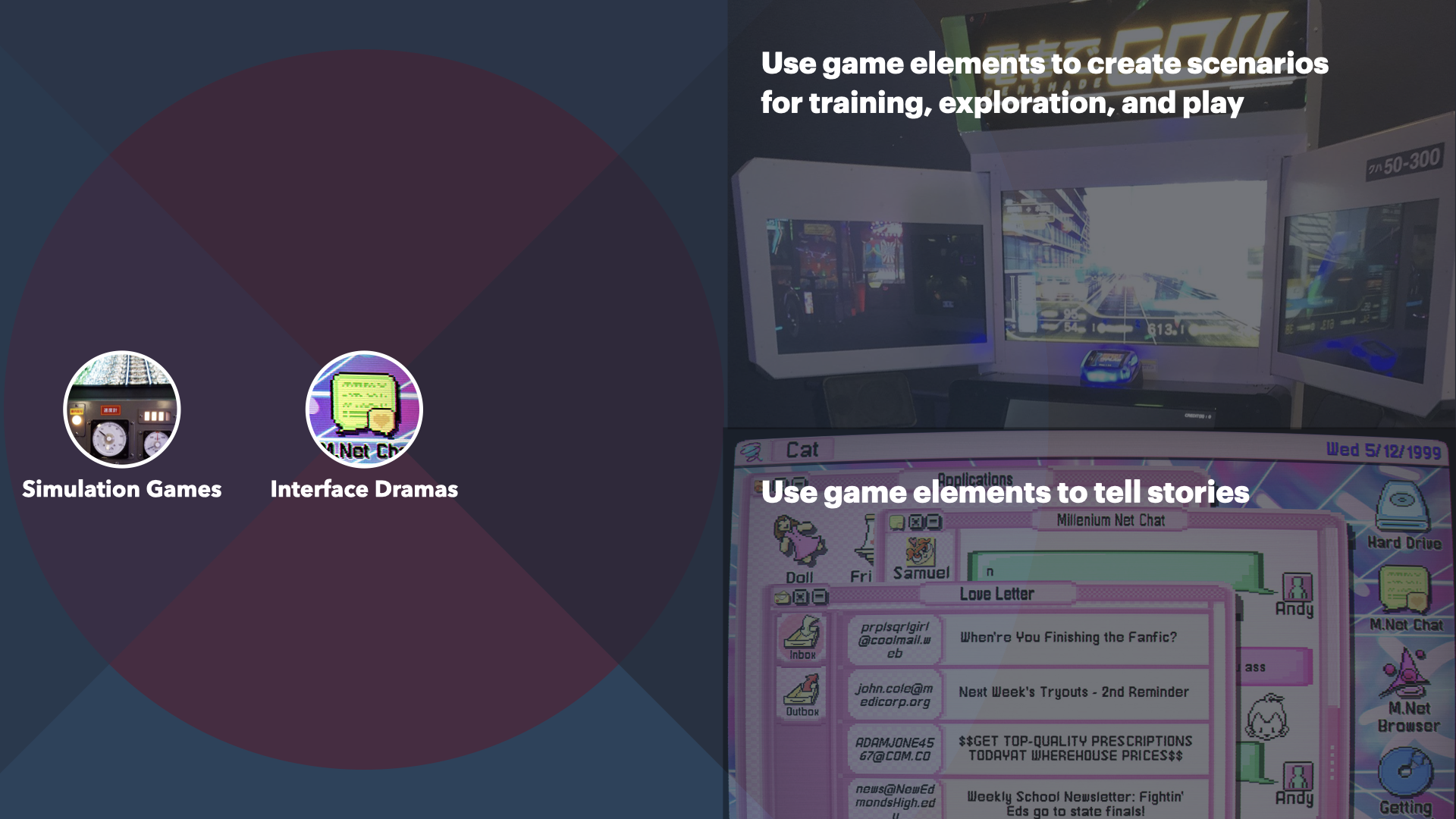

Simulation games and interface dramas both mimic real life things. But they serve different purposes.

For simulation games, they are often played so that players can experience something they wouldn’t otherwise be able to do like fly an airplane, drive a train, or power wash an old house.

For interface dramas, the purpose is to tell stories. Readers uncover clues because they want more story, rather than want to be the best at “using a Windows interface.” Ideally, interface dramas can be played by people who are passingly familiar with computers, and do not need a high level of skill or concentration to complete the game.

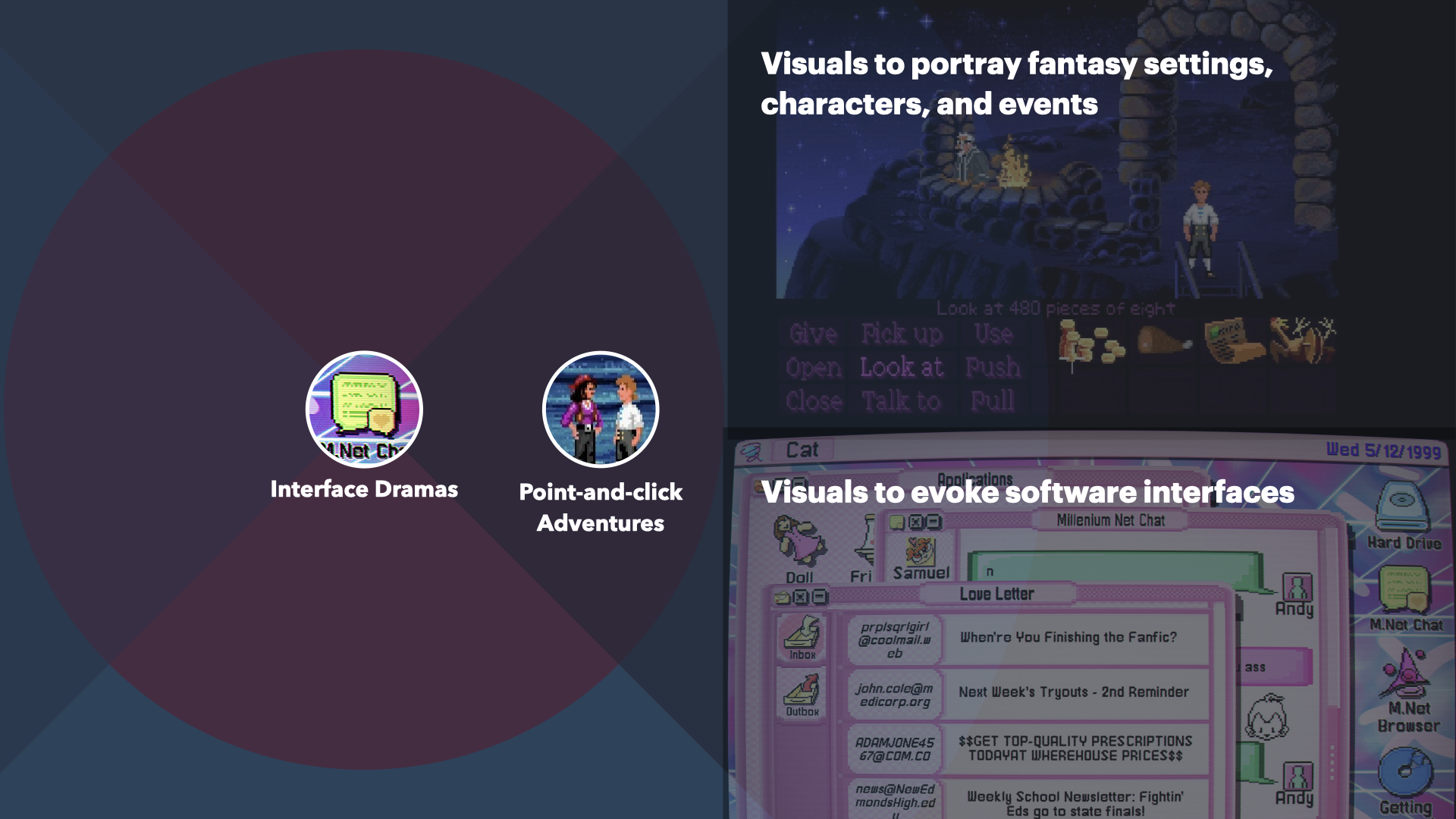

Point and click adventure games and interface dramas both tell stories and pose puzzle challenges using visuals, but the kind of pictures on screen are much different.

Adventure games portray fantasy worlds in lush detail, whereas interface dramas portray software—sometimes in intentionally low detail in order to evoke a mood or a time period. There are adventure games and RPGs that use "hacking" mechanics where one has to use an interface to solve a puzzle, but if more than 80% of the game is played through an interface, it is an interface drama.

We’re not the first ones to try to name this genre. There are already some pre-existing labels, but we prefer interface drama. Here’s why we think our label is better.

Desktop Simulators - it’s too narrow. Not all interfaces are desktops. It also alludes to simulation games which are not usually story driven.

UI Game - it’s too generic. Lots of games have UIs, or even focus strongly on the UI. Would Space Team count? To me, the heart of games like Secret Little Haven is the story. The Drama.

Why should you care about interface dramas?

mabbees: So we've talked about what interface dramas are, and distinguished them from other genres of games. Why should you play them?

CJ: They're easy to learn. You can jump right in! If you know how to use a smartphone, you know how to play SIMULACRA.

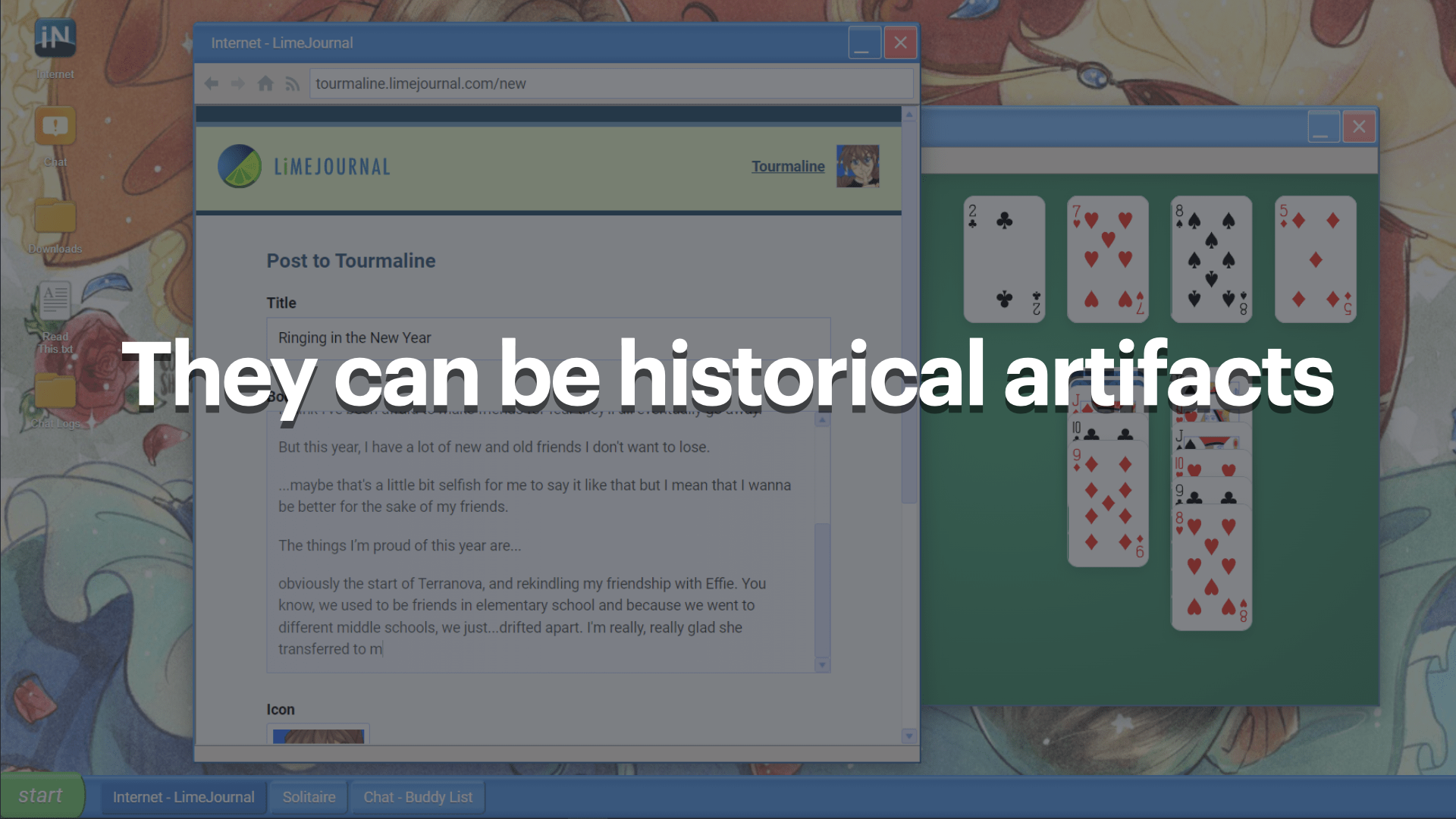

They can be historical artifacts. Our game Terranova is set in the year 2004, so it uses the design vocabulary of the day— things like Windows XP, Solitaire, and early web 2.0 sites like LiveJournal. The game helps preserve some of those things in a kind of time capsule. You can no longer use LiveJournal the same way it was back in 2004. The site has long since changed its look. But our in-game version, LimeJournal, keeps the spirit alive.

mabbees: They’re new and fresh. The genre is still young, and still in some ways figuring itself out.

Interface dramas tell a more diverse range of stories than the power fantasy tropes that pervade a lot of main-stream games.

In the interface dramas we’ve played we’ve come out to our parents, we’ve come of age, we’ve taken on big corporations and stuck it to the Man, we solved cold cases, and we went toe to toe with a haunted smartphone. The recent interface dramas tell interesting stories we’ve never seen before, and we’ve been playing games for a long time. And also oftentimes very QUEER!

CJ: They’re really fun! They’re really fun. Do you want to take care of an “egg friend?” Post your spicy role-play on Limejournal? Hack the inner workings of your computer? Interface dramas let you do things you used to do in Web 1.0—but they also let you do things you could never do in software.

mabbees: Not legally, anyway.

So that brings us back to the question—what is our game, Terranova?

CJ: Terranova is an interface drama. It uses an old Windows XP interface to tell the stories of four high school girls in the year 2004. They go to school. They stay up until 2AM. They struggle with loving who they want to love.

mabbees: It’s a story about growing up, coming out, and realizing that you’re not alone. All in a tiny chatbox.

CJ: Thank you for listening.

mabbees: If you want to get your hands on some interface dramas, well...have we the list for you. Here they are!

This isn’t an exhaustive list, but it contains many of the games we mentioned in this talk. And our game is Terranova at playterranova.com.

Thank you.

After some consideration, we ended up taking IMMORTALITY off the master list because while it features UI as a plot device, it does not feature as a diegetic piece of software, which is one of the main themes of interface dramas. As such, it was taken off the master list, but has an honorable mention in our hearts.

More talks about this genre...

After publishing this, other fine folks shared their own talks. It goes to show that this is an emergent genre and that people are taking notice of this new type of game.

- Inbox Games: Poetics and Authoring Support by Chris Martens and Robert J. Simmons in 2021 at the International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling (ICIDS) (talk | paper)

- Fantasy Filing Systems by Lee Tusman in July 2022 at Narrascope (slides | list)

- Old Interfaces, New Stories by Katherine Morayati & Ian Michael Waddell in August 2022 through Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation (video | slides)